How the world’s most dominant EV market achieved historic penetration while destroying profitability—and what happens when subsidies end in January 2026

In October 2025, China’s new energy vehicle (NEV) industry crossed a threshold that would have seemed impossible just a decade ago. During the first 19 days of the month, NEVs captured 56.1% of all passenger vehicle sales, marking the consolidation of electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles as the dominant force in the world’s largest automotive market. This achievement represents the culmination of a 15-year industrial policy campaign that transformed China from a laggard in internal combustion technology into the undisputed global leader in electric mobility.

Yet this historic success conceals a deepening crisis. The same competitive dynamics that propelled NEVs to market dominance have simultaneously undermined the industry’s financial sustainability. Average profit margins across China’s automotive sector collapsed to 4.3% in 2024, down from nearly 8% in 2017, according to data from the China Passenger Car Association cited by CNN. Manufacturing capacity utilization hovers around 50%, as reported by Morningstar, indicating massive overcapacity that continues to fuel destructive price competition.

This paradox—achieving market dominance while destroying profitability—now faces its most severe test. On January 1, 2026, the Chinese government will begin phasing out the purchase tax exemptions that have supported NEV sales since 2014. The industry’s response to this policy shift, combined with ongoing consolidation pressures, will determine whether China’s electric vehicle sector can transition from subsidy-dependent growth to sustainable commercial viability.

The Architecture of Success: $230.9 Billion in Government Support

China’s NEV dominance did not emerge organically from market forces. It was engineered through one of the most comprehensive industrial policy campaigns in modern economic history. According to research published by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in June 2024, the Chinese government provided cumulative support totaling $230.9 billion to the electric vehicle sector between 2009 and 2023.

This support took five primary forms: nationally approved buyer rebates, exemption from the standard 10% vehicle purchase tax, government funding for charging infrastructure, research and development programs for EV makers, and government procurement of electric vehicles. The buyer rebates and sales tax exemptions accounted for the vast majority of this support, directly reducing the purchase price gap between NEVs and conventional vehicles.

The scale of support evolved dramatically over time. During the initial phase from 2009 to 2017, annual funding averaged approximately $6.74 billion as the sector established its foundation. Support roughly tripled during 2018-2020 as the industry scaled rapidly, then increased again sharply from 2021 onward as China pursued market dominance. CSIS researchers emphasize that their $230.9 billion figure represents a “conservative estimate” that excludes four additional categories of support: local government rebate programs, subsidized land and electricity and credit, direct equity investments by municipal and provincial governments, and subsidies to battery manufacturers and other supply chain participants.

The impact of this support on battery manufacturers illustrates the broader ecosystem effects. CATL, which held a 43.1% share of the Chinese battery market and 36.8% of the global market in 2023, saw its government subsidies increase from $76.7 million in 2018 to $809.2 million in 2023, according to the company’s annual reports cited by CSIS. EVE Energy, China’s fourth-largest battery maker, received $208.9 million in subsidies in 2023 alone.

This comprehensive support system created the conditions for explosive growth. China’s NEV market share stood at just above 1% in 2015, according to Xinhua News Agency. By July 2024, NEVs captured 51.1% of the market for the first time, with 878,000 units sold that month. As Zheng Yun, senior partner and Asia head of automotive practice at Roland Berger, told Xinhua: “This is the beginning of a ‘qualitative change’ in the NEV market.”

The momentum has continued through 2025. According to CnEVPost data published October 22, NEV retail sales reached 632,000 units during October 1-19, representing 56.1% market penetration. Year-to-date through October, NEV retail sales totaled 9.5 million units, up 23% year-over-year, with market penetration of 52.4%.

The Price of Dominance: Profit Collapse and Quality Degradation

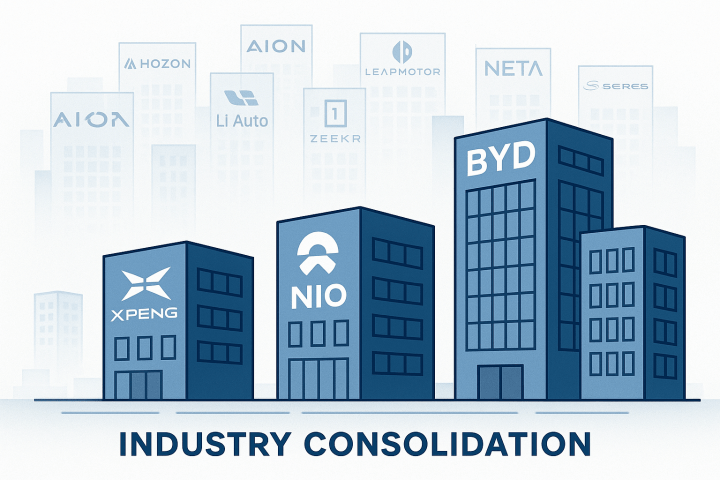

The subsidy-fueled expansion created a crowded marketplace that quickly became unsustainable. At their peak around 2019, nearly 500 domestic automotive brands operated in China. Today, more than 150 Chinese brands and over 50 EV makers continue to battle for survival, according to HSBC research cited by CNN. AlixPartners projects that of the 129 brands currently selling NEVs, only 15 will achieve financial viability by 2030, with these survivors capturing approximately 75% of total market share.

This overcrowding triggered brutal price competition that has persisted for years. The financial consequences have been severe. The China Passenger Car Association data shows average profit margins falling by nearly half over seven years, from 8% to 4.3%. But even this dramatic decline understates the crisis facing many manufacturers. As Shen Hong, an economics researcher at a Peking University think tank that advises the government, told CNN: “A lot of EV makers are actually running at a loss right now. Most of their money comes from industrial funds or social capital, and they just keep raising new rounds to cover those losses.”

The price wars have created a vicious cycle that extends throughout the supply chain. Carl Cheng, an insurance manager for an EV maker, explained to CNN that automakers routinely demand that suppliers deliver at least 10% price discounts annually. “Suppliers have little choice but to quietly accept unfavorable terms,” Cheng said. “If you walk away, there are plenty of others ready to step in.”

The consequences extend beyond financial pressure to affect product quality. Cheng noted that “the overall quality of components of cars has undeniably declined.” In extreme cases, suppliers have been forced to cut prices by more than 40% just to maintain contracts. An anonymous coating materials supplier based in Wuhan told CNN: “If you can’t cut costs anywhere else, what’s left? You cut wages. You bring in temporary workers, push overtime, squeeze out more efficiency – that’s basically all you can do.” This particular supplier had been forced to reduce worker pay by approximately 30%.

The financial strain extends to payment terms as well. Many major Chinese carmakers employ supply chain financing arrangements that result in extended payment cycles, shifting financial risk onto their partners. While Beijing issued rules in 2025 forcing carmakers to pay suppliers within 60 days, industry experts note that manufacturers can circumvent these requirements through the use of promissory notes, which many already do.

The human cost of this competition became visible in high-profile failures. Ji Yue, a joint venture between internet giant Baidu and leading automaker Geely founded in 2021, collapsed in late 2024 despite having deep-pocketed backers and rising sales. Li Hongxing, who ran a social media advertising agency and had borrowed heavily to cover advertising costs for Ji Yue, told CNN the failure left him with debts of 40 million yuan ($5.6 million): “It was a feeling of sheer despair.”

The Policy Cliff: Subsidy Phase-Out and Industry Pushback

Against this backdrop of financial stress, the Chinese government has decided to begin withdrawing the support that enabled the industry’s growth. The current policy, in effect through the end of 2025, provides full exemption from the standard 10% vehicle purchase tax, with the benefit capped at RMB 30,000 ($4,210) per vehicle. This exemption has been a cornerstone of NEV policy since 2014.

The planned transition, scheduled to begin January 1, 2026, would reduce the exemption to a 5% tax rate (half the standard rate) with a maximum reduction of RMB 15,000. This policy would remain in effect through 2027, after which the full 10% tax would presumably apply. For a vehicle priced at RMB 300,000 ($42,000), this represents an immediate price increase of RMB 15,000 ($2,100) on January 1, 2026, followed by another RMB 15,000 increase on January 1, 2028.

The industry has responded with alarm. Chen Shihua, deputy secretary-general of the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM), publicly called for a more gradual phase-out in comments reported by CnEVPost on October 25. Chen proposed implementing a 3% tax rate in 2026 and 7% in 2027, instead of the planned 5% for both years. This would reduce the immediate price shock by RMB 6,000 ($840) per vehicle in 2026.

Chen’s rationale reflects the industry’s precarious financial position. He noted that “China’s auto industry continues to face slow domestic demand growth, ongoing inventory pressures requiring cautious management, and sustained pressure on industry profitability.” He cited “risks from price wars persist, geopolitical tensions disrupt supply chain stability, and the sector continues to face significant operational pressures.”

The timing of the subsidy phase-out coincides with broader economic challenges in China. The automotive sector employs more than 4.8 million people according to CEIC data cited by CNN, making mass consolidation politically sensitive. As Chetan Ahya, chief Asia economist at Morgan Stanley, told CNN: “Those are definitely good starting steps, and that needs to happen. But just cutting capacity will not be a perfect solution, there is going to be a social stability problem if you just decide to stop investing.”

Corporate Response: Manufacturer Subsidies as Stopgap

Facing the impending policy shift, major NEV manufacturers have begun implementing their own subsidy programs to cushion the impact on sales. These corporate subsidies effectively extend government support through private means, though at significant cost to already-stressed profit margins.

Xiaomi, which entered the NEV market in 2024, announced in late October that it would offer subsidies of up to RMB 15,000 for customers who place orders by November 30, 2025. This subsidy exactly matches the reduction in government support scheduled for January 2026, effectively holding consumer prices constant through the transition.

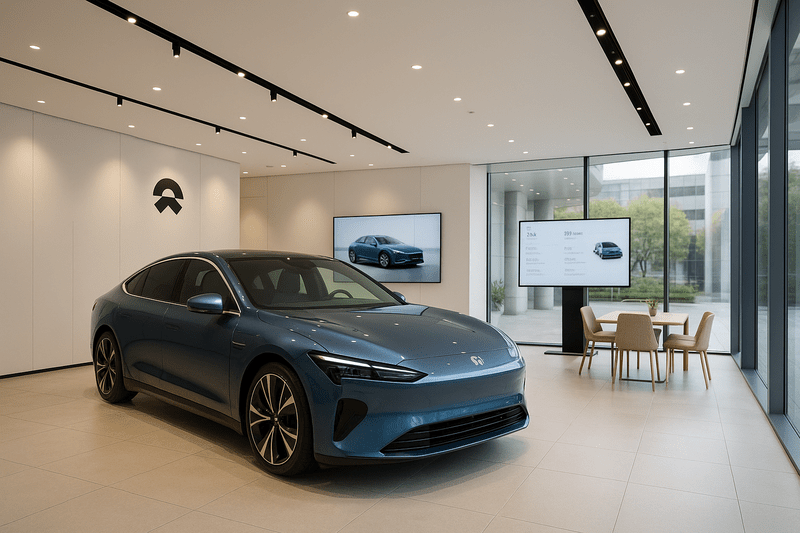

Nio, a leading premium EV maker, implemented a similar program for its ES8 model. After launching the vehicle on September 20, Nio sold out its initial 40,000-unit allocation and announced RMB 15,000 subsidies for deliveries scheduled in 2026, according to CnEVPost reporting from October 24. Li Auto announced subsidies for its Li i6 model for orders placed before October 31.

These programs serve multiple strategic purposes. Most immediately, they pull forward demand from 2026 into late 2025, allowing manufacturers to maintain sales momentum and production schedules. They also help manufacturers gauge price sensitivity and competitive dynamics before the policy change takes full effect. Finally, they signal to consumers that major brands will absorb at least some of the cost increase, potentially preventing a market-wide demand shock.

However, the sustainability of manufacturer-funded subsidies remains questionable given the industry’s profit margins. Carl Cheng, the insurance manager, told CNN: “Compared with before, I don’t think the current price war has eased much at all. The reality is that newly launched models with lower prices draw in plenty of orders… at the end of the day automakers have to focus on survival.”

Market Dynamics: Strong Sales Masking Structural Weakness

Current sales data presents a paradox: the market appears robust even as the industry faces existential pressures. Through October 19, 2025, NEV retail sales reached 632,000 units, up 5% year-over-year and 2% month-over-month, according to CnEVPost. Year-to-date retail sales of 9.5 million units represent 23% growth compared to 2024. Wholesale volumes show even stronger growth, with year-to-date wholesale reaching 11.12 million units, up 30% year-over-year.

However, these headline figures mask concerning details. During October 1-12, NEV retail sales of 367,000 units actually declined 1% year-over-year, suggesting momentum may be weakening. More significantly, total passenger vehicle sales (including conventional vehicles) fell 6% year-over-year during October 1-19, indicating that NEV growth is occurring within a contracting overall market.

The divergence between NEV and conventional vehicle performance has become dramatic. In July 2024, NEV sales grew 36.9% year-over-year while traditional fuel vehicle sales declined 26%, according to Xinhua. This suggests that NEV adoption is partly driven by substitution from conventional vehicles rather than pure market expansion.

Liu Jia, an electronics and automotive analyst at Nomura Orient International Securities, told Xinhua that “demand-driven rather than policy-driven has become the main factor boosting the sales of domestic NEVs.” This assessment reflects genuine improvements in NEV technology, including enhanced battery range, expanded charging infrastructure (10.24 million charging piles by June 2024, up 54% year-over-year according to Xinhua), and better integration of digital features.

Yet the timing of the subsidy phase-out will test whether this demand is truly independent of price support. The RMB 15,000 price increase represents approximately 5% of the cost of a mid-range NEV priced at RMB 300,000. In a market where manufacturers compete on razor-thin margins and consumers have become accustomed to aggressive discounting, even this modest increase could significantly impact demand.

The Global Dimension: Export as Escape Valve

Facing overcapacity and profit pressure at home, Chinese NEV manufacturers have increasingly looked to international markets as an outlet for production. Chinese automotive exports reached nearly 6 million vehicles in 2024, more than any other country, according to CNN. This export surge has become a critical component of industry strategy, offering manufacturers a potential path to utilize excess capacity and escape domestic price wars.

AlixPartners projects that Chinese automakers will double their European market share to 10% by 2030. The consulting firm forecasts that Chinese manufacturers will boost annual production in Europe by 800,000 vehicles by 2030, while European counterparts could shutter 400,000 units of capacity, equivalent to 1.5 production plants. This expansion reflects both the competitiveness of Chinese NEVs and the strategic necessity of localizing production to avoid trade barriers.

However, the export pathway faces significant obstacles. The United States, European Union, Canada, and Mexico have all implemented tariffs or restrictions on Chinese EVs. AlixPartners estimates that new U.S. tariffs will impose costs of approximately $30 billion for 2026. On September 27, 2025, China tightened EV export rules by requiring licenses for carmakers to ship overseas starting in 2026, aimed at addressing foreign concerns about dumping of low-priced vehicles.

Yichao Zhang, partner of the Greater China Automotive Practice at AlixPartners, noted in the firm’s July 2025 report that “Chinese OEM exports have slowed due to tariffs and geopolitical uncertainty, but the export of China’s ‘New Operating Model’—driven by partnerships and joint ventures—is gaining traction.” This model, which enables automakers to bring vehicles to market twice as fast with 40-50% less investment and a 30% cost advantage, represents a potentially more durable form of competitive advantage than simple price competition.

Three Scenarios: Consolidation, Stabilization, or Demand Shock

As the January 2026 subsidy phase-out approaches, three broad scenarios appear possible, each with distinct implications for the industry’s evolution.

Scenario One: Accelerated Consolidation. In this scenario, the subsidy reduction triggers a wave of failures among financially weak manufacturers, accelerating the consolidation that AlixPartners and other analysts view as inevitable. Weaker brands lose market share rapidly as they lack the financial resources to absorb the subsidy reduction or compete with better-capitalized rivals. The 15 financially viable brands identified by AlixPartners emerge more quickly than expected, potentially by 2028 rather than 2030. This consolidation reduces overcapacity, allowing surviving manufacturers to improve pricing power and profit margins. However, it also results in significant job losses and potential social instability, forcing government intervention to manage the transition.

Scenario Two: Managed Stabilization. Under this scenario, a combination of manufacturer subsidies, gradual policy adjustments (potentially including adoption of Chen Shihua’s proposed slower phase-out), and modest price increases allows the market to adjust without a major disruption. Demand softens but does not collapse, declining perhaps 10-15% in early 2026 before stabilizing. The consolidation process continues but at a measured pace, with 3-5 brands failing per year rather than a sudden wave of bankruptcies. This outcome requires continued financial support from parent companies and investors, as well as government willingness to slow the subsidy phase-out if market stress becomes severe. It represents the path of least resistance politically but prolongs the industry’s financial stress.

Scenario Three: Demand Shock and Market Correction. In this more pessimistic scenario, the subsidy reduction coincides with broader economic weakness to produce a sharp decline in NEV demand. Consumers, facing economic uncertainty and higher vehicle prices, delay purchases or opt for cheaper conventional vehicles. NEV sales decline 25-35% in the first half of 2026, forcing manufacturers to implement emergency price cuts that further erode profitability. Multiple mid-tier brands fail simultaneously, creating supply chain disruptions and consumer confidence problems. The government is forced to intervene with emergency support measures, potentially including restoration of some subsidy programs or accelerated consolidation through directed mergers.

What the Data Suggests: A Managed but Painful Transition

The available evidence points most strongly toward Scenario Two—a managed but painful stabilization—though with significant risk of sliding into Scenario Three if economic conditions deteriorate or policy execution falters.

Several factors support the managed stabilization scenario. First, the Chinese government has demonstrated consistent commitment to the NEV sector as a strategic priority, making abrupt withdrawal of all support unlikely. Chen Shihua’s public call for a more gradual phase-out may signal government receptiveness to policy adjustments if market stress becomes severe. Second, major manufacturers have shown willingness to absorb significant costs to maintain market position, as evidenced by the manufacturer subsidy programs. Third, the underlying technology and infrastructure improvements are real—NEVs genuinely offer compelling advantages in urban Chinese markets, suggesting that demand has some foundation beyond pure subsidy dependence.

However, multiple risk factors could push the outcome toward a more severe correction. The profit margin data is particularly concerning. At 4.3% average margins with many manufacturers operating at losses, the industry has limited capacity to absorb additional financial stress. The 50% capacity utilization rate indicates that overcapacity remains severe despite years of consolidation discussion. The supply chain stress described by Carl Cheng and others suggests that financial fragility extends throughout the ecosystem, not just to vehicle manufacturers.

The October sales data showing year-over-year decline during the first 12 days of the month, followed by recovery in the latter period, may indicate that consumers are already responding to the impending policy change by accelerating purchases. If this interpretation is correct, January 2026 could see a significant demand gap as this pulled-forward demand disappears.

Dr. Stephen Dyer, Asia Leader of the Automotive and Industrial Practice at AlixPartners, summarized the challenge in the firm’s July 2025 report: “This environment has driven remarkable advances in technology and cost efficiency, but it has also left many companies struggling to achieve sustainable profitability. As growth slows at home and global trade barriers rise, Chinese EV makers must focus on building strong brands, investing in advanced technologies like autonomous driving, and localizing operations in key international markets. Only those who can adapt quickly, scale efficiently, and navigate both domestic and global headwinds will continue to thrive on the world stage.”

Broader Implications: Testing China’s Industrial Policy Model

The NEV industry’s transition from subsidy dependence to commercial viability represents more than a sectoral challenge. It serves as a test case for China’s broader industrial policy approach, which has relied heavily on government support to build strategic sectors including solar panels, semiconductors, and artificial intelligence.

The NEV sector demonstrates both the strengths and limitations of this model. On the positive side, comprehensive government support successfully created a globally competitive industry from scratch in just 15 years. China now dominates EV manufacturing, battery production, and charging infrastructure. The sector has driven innovation in battery chemistry, electric drivetrains, and vehicle software integration. As Wang Honglin, a research fellow at China Academy of Financial Research at Shanghai Jiaotong University, told Xinhua: “The rising NEV industry is changing the auto industry completely, as well as the landscape of the whole manufacturing sector across the globe.”

However, the model’s weaknesses have also become apparent. The combination of subsidies and local government competition created massive overcapacity that has proven difficult to eliminate. The focus on market share and production volume rather than profitability has resulted in an industry that remains financially fragile despite its technical capabilities. The difficulty of withdrawing support without triggering market disruption suggests that subsidy dependence, once established, becomes difficult to reverse.

Chinese leadership has recognized these challenges. In a Communist Party magazine article published in September 2025, President Xi Jinping called for “cracking down on chaotic, cut-throat price wars among companies,” according to CNN. The government has implemented multiple measures to address “involution” (neijuan)—excessive, self-defeating competition that yields little progress. These include summoning auto leaders to warn against price wars, issuing payment cycle rules, and releasing guidelines urging local governments to scale back subsidies and eliminate overcapacity.

Yet industry experts remain skeptical that administrative measures alone can resolve the structural overcapacity. Shen Hong, the Peking University researcher, told CNN: “When it comes to price wars, it’s just not very realistic to think they can be completely curbed through administrative measures.”

The Road Ahead: Defining Questions for 2026

As the January 2026 subsidy phase-out approaches, several questions will determine the industry’s trajectory:

Will the government adjust the phase-out timeline? Chen Shihua’s public proposal for a more gradual transition may be testing political receptiveness to policy modification. If early 2026 sales data shows significant demand weakness, the government may implement emergency adjustments. However, such changes would undermine the credibility of the phase-out policy and potentially prolong the industry’s subsidy dependence.

Can manufacturer subsidies bridge the transition? Major brands have committed to absorbing the subsidy reduction for vehicles ordered in late 2025. Whether they can sustain this support through 2026 depends on their financial reserves and investor patience. If manufacturer subsidies prove unsustainable, a mid-year price increase could trigger the demand shock that the programs were designed to prevent.

How will consumers respond to higher prices? The critical unknown is price elasticity of demand in the Chinese NEV market. If consumers have genuinely shifted preference toward NEVs based on technology and operating cost advantages, the RMB 15,000 price increase may have limited impact. If purchase decisions remain highly price-sensitive, demand could decline sharply.

Which brands will fail first? AlixPartners projects that 114 of 129 current NEV brands will not achieve financial viability by 2030. The subsidy phase-out will likely accelerate this consolidation. The identity and timing of failures will significantly impact supply chains, employment, and consumer confidence.

Can exports offset domestic pressure? International expansion offers a potential outlet for excess capacity, but faces significant trade barriers. Whether Chinese manufacturers can successfully localize production in key markets while maintaining cost advantages will partly determine the industry’s long-term viability.

The answers to these questions will emerge over the coming months. What is already clear is that China’s NEV industry, having achieved the historic milestone of market dominance, now faces the more difficult challenge of achieving financial sustainability. The $230.9 billion in government support successfully created a globally competitive industry. Whether that industry can survive the withdrawal of support will determine if China’s industrial policy model can produce not just technical capability, but durable commercial success.

Cui Dongshu, secretary general of the China Passenger Car Association, told Xinhua: “The trend of the times demands a rapid shift toward electrification and intelligence in the auto industry. As internet and AI technologies integrate into vehicles, they will unlock new possibilities.” The question is whether China’s NEV makers can realize these possibilities while simultaneously achieving the profitability that has eluded them during their rapid ascent to market dominance.

References

1.CnEVPost. (2025, October 22). “China NEV retail at 632,000 in Oct 1-19, up 5% year-on-year.” Lei Kang. https://cnevpost.com

2.CnEVPost. (2025, October 25). “CAAM deputy secretary-general calls for China to phase out NEV tax incentives more gradually.” Phate Zhang. https://cnevpost.com

3.CnEVPost. (2025, October 24). “Xiaomi EV becomes latest to offer subsidies to offset impact of China’s tax incentive retreat.” Lei Kang. https://cnevpost.com

4.Liu, J., & Yang, H. (2025, September 29). “Chinese electric cars are going global. A cut-throat price war at home could kill off many of its brands.” CNN Business. https://www.cnn.com/2025/09/26/cars/chinese-electric-cars-price-wars-intl-hnk-dst

5.Xinhua News Agency. (2024, August 16). “China’s NEV industry speeds up for greener, smarter future.” https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202408/16/content_WS66bf0ee3c6d0868f4e8e9fc7.html

6.Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2024, June 20). “The Chinese EV Dilemma: Subsidized Yet Striking.” Trustee China Hand. https://www.csis.org/blogs/trustee-china-hand/chinese-ev-dilemma-subsidized-yet-striking

7.AlixPartners. (2025, July 3). “AlixPartners 2025 Global Automotive Outlook: China’s ‘New Operating Model’ Redefines Speed, Efficiency, and Market Leadership in Automotive Industry.” https://www.alixpartners.com/newsroom/2025-alixpartners-global-automotive-outlook-china/